Reflux Treatment

Reflux Overview

Gastroesophageal reflux, also called “acid reflux,” occurs when the stomach contents back up into the esophagus and/or mouth. Occasional reflux is normal and can happen in healthy infants, children, and adults, most often after eating a large meal. Most episodes are brief and do not cause bothersome symptoms or complications.

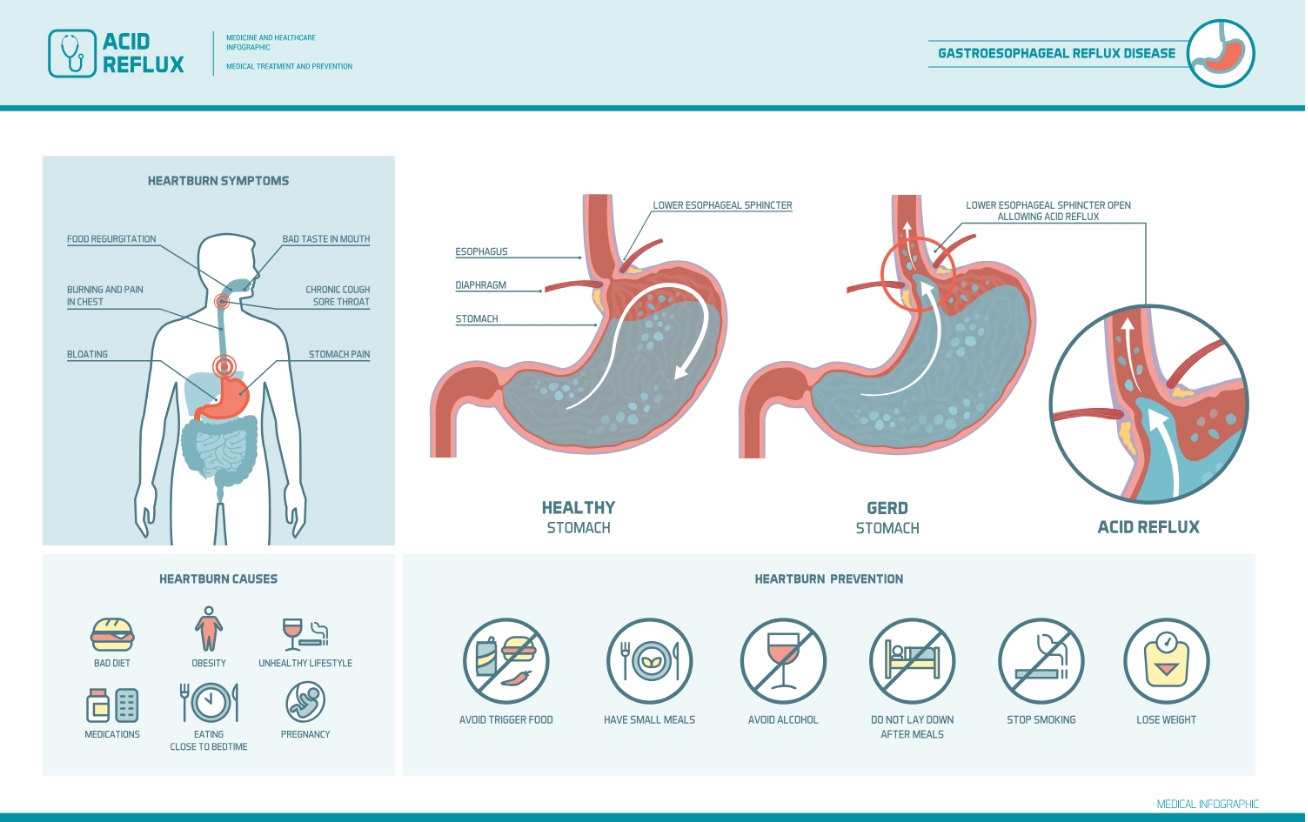

By contrast, people with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD or GORD) experience bothersome symptoms or damage to the esophagus as a result of acid reflux. Symptoms of GERD can include heartburn, regurgitation, and difficulty or pain with swallowing.

What Happens in Acid Reflux and GERD

When you eat, food is carried from your mouth to your stomach through the esophagus, a tube-like structure that is approximately 10 inches long and 1 inch wide in adults. The esophagus is made of tissue and muscle layers that expand and contract to propel food to your stomach through a series of wave-like movements called peristalsis.

At the lower end of the esophagus, where it connects to the stomach, there is a circular ring of muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). After you swallow, the LES relaxes and opens to allow food to enter your stomach, where it mixes with acids that help with digestion. The LES then contracts shut to prevent the food and acid from backing up into your esophagus.

However, sometimes the LES relaxes inappropriately; this allows liquids in the stomach to wash back into the esophagus. This happens occasionally to everyone. Most of these episodes occur shortly after meals, are brief, and do not cause symptoms. Normally, reflux should rarely occur during sleep.

In some people, acid reflux causes bothersome symptoms or injury to the esophagus over time; when this happens, it is considered GERD. In general, damage to the esophagus is more likely to occur when acid refluxes frequently, the stomach contents are very acidic, or the esophagus is unable to clear away the acid quickly.

GERD Risk Factors

Certain things increase a person’s risk of developing GERD, including:

- Hiatus hernia – This is a condition in which part of the upper stomach pushes up through the diaphragm (the large, flat muscle at the base of the lungs). The diaphragm has an opening for the esophagus to pass through before it joins with the stomach (called the “diaphragmatic hiatus”); in people with a hiatal hernia, part of the stomach also squeezes up through this hole.

- Obesity – People who are obese or overweight have an increased risk of GERD. While the reasons for this are not completely understood, it is partially related to increased pressure in the abdomen.

- Pregnancy – Many women experience acid reflux during pregnancy. This usually resolves after delivery, and complications are rare.

- Lifestyle factors and medications – Some foods (including fatty foods, chocolate, and peppermint), caffeine, alcohol, and cigarette smoking can all cause acid reflux and GERD. Certain medications also increase the risk.

GERD Symptoms

The most common symptoms of GERD are:

Heartburn – This typically feels like a burning sensation in the centre of the chest, which sometimes spreads to the throat. It most often happens after a meal.

Regurgitation – This is when stomach contents (acid mixed with bits of undigested food) flow back into your mouth or throat.

Other symptoms of GERD may include:

- Stomach pain (pain in the upper abdomen)

- Chest pain

- Difficulty swallowing where food gets stuck in the esophagus (called dysphagia) or pain on swallowing (called odynophagia)

- Persistent laryngitis/hoarseness (due to the acid irritating the vocal cords)

- Persistent sore throat or cough

- Sense of a lump in the throat

- Nausea and/or vomiting

Over time, GERD can lead to complications. These include problems related to esophageal damage as well as other issues.

When to seek help

The following signs and symptoms may indicate a more serious problem. Tell your doctor right away if you:

- Have difficulty or pain with swallowing (eg, feeling like food gets stuck in your throat)

- Have no appetite or lose weight without trying

- Have chest pain

- Feel like you are choking

- Have signs of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract, such as blood in your vomit or dark-colored vomit that looks like coffee grounds or black stools

- Have persistent vomiting

- Have new stomach pain and are age 60 or older

Call us today for an appointment at Gledswood Hills or Shellharbour

GERD Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GERD is based on your symptoms as well as other risk factors.

Diagnosis based on symptoms

If you have the “classic” symptoms of GERD (heartburn and/or regurgitation) your doctor may be able to diagnose you with GERD based on this alone. In this situation, they will likely suggest a trial of medication; if your symptoms improve, it is likely that GERD was the cause.

Additional testing

You may be recommended additional evaluation and testing if you:

- Do not have an improvement in symptoms after taking a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)

- Do not have the classic symptoms of GERD (heartburn or regurgitation)

- Have symptoms that may indicate a more serious problem

- Have risk factors for certain complications such as Barrett’s esophagus

It is important to rule out potentially life-threatening problems that can cause symptoms similar to those of GERD. For example, chest pain can also be a symptom of heart disease and should be evaluated immediately. Once these have been ruled out and the diagnosis of GERD is not clear, you will likely be recommended one or more of the following tests.

An upper endoscopy is a test that allows a doctor to directly examine the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract . A small, flexible tube is passed into the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. The tube has a light source and a camera that displays magnified images on a monitor. Damage to the lining of the GI tract can be evaluated and samples of tissue (biopsies) can be taken to determine the extent of tissue damage.

An esophageal pH study is the most direct way to measure the frequency of acid reflux. The test involves inserting a thin tube with a sensor through the nose and into the esophagus (which is left in place for 24 hours); an alternative approach involves placing a wireless sensor, which adheres to the esophageal lining, into your esophagus during an upper endoscopy. During the next one to four days, you will be asked to keep a diary of your symptoms. The sensor measures how often stomach acid is reaching your esophagus. Your provider can use this information to determine the frequency of reflux and how this relates to your symptoms.

This test may be used to confirm a diagnosis of GERD if you continue to have symptoms, especially if you have tried taking a PPI. It can also be used to monitor how well treatment is working.

Esophageal manometry involves having a tube that measures the pressure from the muscle contractions placed in your esophagus. This can help to determine if the lower esophageal sphincter is functioning properly. It may be done if you have chest pain and/or difficulty swallowing but your upper endoscopy results are normal; this can help diagnose motility disorders (problems with how the muscles in the GI tract work to digest food).

GERD Complications

Most people with GERD will not develop serious complications, especially if they get treatment. However, potentially serious complications can sometimes happen in people with severe GERD.

This is when the esophageal lining is damaged as a result of exposure to stomach acid. This can lead to erosions or ulcers, which may bleed. Bleeding from ulcers is not always visible, but it can be detected with stool tests.

Damage from acid can cause the esophagus to scar and narrow, causing a partial blockage (stricture) that can cause food or pills to get stuck in the esophagus. The narrowing is caused by scar tissue that develops as a result of ulcers that repeatedly damage and then heal in the esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus occurs when the normal cells that line the lower esophagus (called squamous cells) are replaced by a different cell type (called intestinal cells). This process usually results from repeated damage to the esophageal lining; longstanding GERD is the most common cause.

The intestinal cells have a small risk of transforming into cancer cells over time. As a result, people with Barrett’s esophagus are advised to have a periodic upper endoscopy to monitor for early warning signs of cancer.

If stomach acid backs up into the throat, this can cause inflammation of the vocal cords, a sore throat, or a hoarse voice. The acid can also be inhaled into the lungs and cause pneumonia or asthma symptoms. Over time, acid in the lungs can lead to permanent lung damage.

Repeated episodes of acid reflux can erode the enamel of the teeth over time.

GERD Treatment

GERD treatment is adjusted to match the frequency and severity of symptoms as well as whether there are complications.

Lifestyle changes

Certain lifestyle and dietary changes can often help relieve symptoms of GERD. If you have mild symptoms, you can try these approaches before seeking medical attention.

If your symptoms are more serious, it’s a good idea to talk to your doctor before making any changes, so they can advise you on how to incorporate these approaches into your treatment plan.

The following lifestyle changes are often recommended

Losing weight may help people reduce acid reflux. In addition, weight loss has a number of other health benefits, including a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Although most people only have heartburn during the two- to three-hour period after meals, some wake up at night with heartburn. People with nighttime heartburn can elevate the head of their bed, which raises the head and shoulders higher than the stomach, allowing gravity to reduce acid reflux and aid in clearing what reflux does occur.

You can raise the head of your bed by putting blocks of wood under the legs or a foam wedge over the mattress. Several companies have developed commercial products for this purpose. However, it is usually not helpful to use additional pillows; this only elevates the head and neck with minimal effect on reflux.

Some foods also cause relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, which can lead to acid reflux. Excessive caffeine, chocolate, alcohol, peppermint, and fatty foods may cause bothersome acid reflux in some people. If you notice that your symptoms are worse after you have certain foods or beverages (trigger foods), it’s reasonable to limit or avoid these things.

Saliva helps to neutralize refluxed acid, and smoking reduces the amount of saliva in the mouth and throat. Smoking also lowers the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter and provokes coughing, causing frequent episodes of acid reflux in the esophagus. In addition to having many other health benefits, quitting smoking can reduce or eliminate symptoms of mild reflux.

While evidence is limited, other changes also sometimes seem to help, such as:

Avoiding late meals – Lying down with a full stomach may increase the risk of acid reflux. By planning meals for at least two to three hours before bedtime, symptoms may be reduced. This is especially true for people with nighttime reflux.

Wearing loose, comfortable clothing – At minimum, tight-fitting clothing can increase discomfort, but it may also increase pressure in the abdomen, promoting hiatus hernia and forcing stomach contents into the esophagus.

Mild Symptoms

In addition to lifestyle changes, the initial treatment of mild GERD includes the use of nonprescription antacids or histamine receptor antagonists.

Antacids neutralise stomach acid and are commonly used for short-term relief of heartburn symptoms. While they start working quickly, the neutralizing effect only lasts for approximately 30 to 60 minutes after each dose. Alginates have a more prolonged effect as the alginate floats to the top of gastric content and keeps newly secreted acid away from the esophageal inlet.

The histamine antagonists reduce production of acid in the stomach. They are more effective than antacids in relieving heartburn, and their effects last for longer; however, they are not usually adequate for the treatment of severe or frequent symptoms.

PPIs are the most effective medications for reducing stomach acid. They include Esomeprazole, Lansoprazole, Pantoprazole, Omeprazole, and Rabeprazole. Some PPIs are available over-the-counter, although higher doses may require a prescription.

Your doctor will determine the optimal dose and type of PPI for you, and you will probably continue taking it for at least eight weeks. More prolonged treatment depends on whether and when symptoms return after cessation:

If your symptoms return within three months of stopping the medication or if you have severe inflammation of your esophagus, long-term treatment is usually recommended. An upper endoscopy (if you haven’t already had one) will also be recommended to rule out other problems.

If your symptoms return three months or more after stopping the medication, you will be recommended another course of PPI treatment. The goal is to take the lowest effective dose of medication that controls symptoms and prevents complications.

PPIs are safe, although they may be expensive, especially if taken for a long period of time. Long-term risks of PPIs may include an increased risk of certain gut infections or reduced absorption of minerals and nutrients. In general, these risks are small. However, even a small risk emphasizes the need to take the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time.

If symptoms do not improve

Some people do not experience complete symptom resolution with PPI treatment. Doctors call this “refractory” GERD or refractory GERD-like symptoms. If you continue to have bothersome symptoms after a course of PPI treatment, your provider may recommend one or more of the following:

- Splitting the dose of PPI (ie, taking two smaller doses rather than one larger dose daily)

- Increasing the PPI dose or switching to a different (more potent) PPI

- Adding other medications

- Further testing to confirm (or refute) the GERD diagnosis and/or rule out other problems

- Considering surgical treatment

Treatment of GERD during pregnancy

Treatment of GERD during pregnancy begins with lifestyle changes. If this does not relieve symptoms, your health care provider may suggest antacids or alginates.

If the above measures are not effective, your provider might recommend a histamine antagonist followed by a PPI if necessary.

Although both classes of medication can generally be given during pregnancy, the general strategy is to avoid all medications during pregnancy if possible.

Surgical Treatment

Because lifestyle changes and medications are very effective in controlling symptoms in most cases, there is a limited role for surgical treatment of GERD. However, it may be an option for certain people whose symptoms are not adequately controlled with other treatments, or who cannot or do not wish to comply with a medication regimen.

In general, “antireflux” surgery involves repairing a hiatal hernia (if present) and strengthening the lower esophageal sphincter. The most common surgical procedure is called laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. This procedure involves wrapping the upper part of the stomach around the lower end of the esophagus.

Following Nissen fundoplication, most people experience symptoms including difficulty swallowing and feeling bloated (called the “gas bloat syndrome”).

These symptoms may resolve over time but can persist. There are other risks associated with surgery as well. Despite this, most people say they are satisfied with the results of the surgery in the long term.

There are other surgical procedures sometimes used to treat GERD as well, including less invasive options.